Depreciation in the cash flow statement can be a bit tricky to understand, but don't worry, I'm here to break it down for you.

Depreciation is a non-cash expense, which means it doesn't directly affect a company's cash flow. According to the article, depreciation is calculated using the straight-line method, where the cost of an asset is spread evenly over its useful life.

In a cash flow statement, depreciation is reported as a non-cash item, which means it's not deducted from cash inflows or added to cash outflows. This is because depreciation doesn't require a company to pay out cash.

If this caught your attention, see: Cash Flow Statement for Non Profit Organisation

What Is Depreciation?

Depreciation is a non-cash expense that allocates the purchase of fixed assets, or capital expenditures, over its estimated useful life.

This means that a company doesn't have to pay the full cost of a fixed asset upfront, but rather spreads it out over time based on its expected lifespan.

The depreciation expense reduces the carrying value of a fixed asset recorded on a company's balance sheet based on its useful life and salvage value assumption.

For example, if a company buys a piece of equipment that's expected to last 5 years, it will depreciate that asset over those 5 years, reducing its value on the balance sheet accordingly.

Depreciation is an important concept in accounting because it allows companies to accurately reflect the value of their assets on their financial statements.

Explore further: Cash Flow Statement Cheat Sheet

Calculating Depreciation

Calculating depreciation is a crucial step in understanding the cash flow statement. The most common methods to calculate depreciation are the Straight-Line Depreciation Method, Declining Balance Depreciation Method (DDB), and Units of Production Depreciation Method.

The Straight-Line Depreciation Method is the simplest method, where you subtract the salvage value of the asset from its full price, and divide that by the expected lifetime of the asset. This results in the amount of depreciation that can be deducted each year, which is $60k in the example where the Capex outflow is right at the beginning of the period (BOP).

You can use the formula to calculate the annual depreciation expense under the straight-line method, which subtracts the salvage value from the total PP&E cost and divides the depreciable base by the useful life assumption. The annual depreciation expense is the allocation of the one-time cash outflow from a capital expenditure (Capex) throughout the useful life of the fixed asset.

In a typical scenario, the depreciation expense comes out to be $60k per year, which will remain constant until the salvage value reaches zero. This is demonstrated in the example where the PP&E balance in 2021 comes from the $300k corresponding Capex spend, and the depreciation expense is $60k per year.

Here are the common inputs for the formula to calculate the annual depreciation expense:

- Annual Depreciation Expense

- Salvage Value

- Useful Life

These inputs are crucial in calculating the depreciation expense accurately. The salvage value is the value of the asset at the end of its useful life, and the useful life is an estimate of how long the asset will continue to be used and be of service to the company.

The formula to calculate the annual depreciation expense is:

Annual Depreciation Expense = (Salvage Value - Total PP&E Cost) / Useful Life

This formula can be used to calculate the depreciation expense for any asset, as long as you have the necessary inputs.

For more insights, see: Annual Net Cash Flow

Methods of Depreciation

There are several methods of depreciation, each with its own unique approach to expensing fixed assets.

The straight-line depreciation method is the most common, gradually reducing the carrying balance of a fixed asset over its useful life.

The useful life of a fixed asset is the estimated number of years it is assumed to continue providing positive economic utility, which can vary depending on the asset.

The straight-line method requires three key pieces of information: purchase price, salvage value, and useful life.

Here are the key factors to consider when using the straight-line method:

- Purchase Price: The cost of acquiring the fixed asset on the original date of purchase.

- Salvage Value: The estimated value of the asset at the end of its useful life.

- Useful Life: The estimated number of years in which the fixed asset is assumed to continue providing positive economic utility.

The double declining balance (DDB) method is a form of accelerated depreciation, where a greater proportion of the total depreciation expense is recognized in the initial stages.

The units of production method recognizes depreciation based on the perceived usage of the fixed asset, but it's the most tedious method and requires granular analysis and per-unit tracking.

The units of production method is technically more accurate, but it's not commonly used due to its complexity.

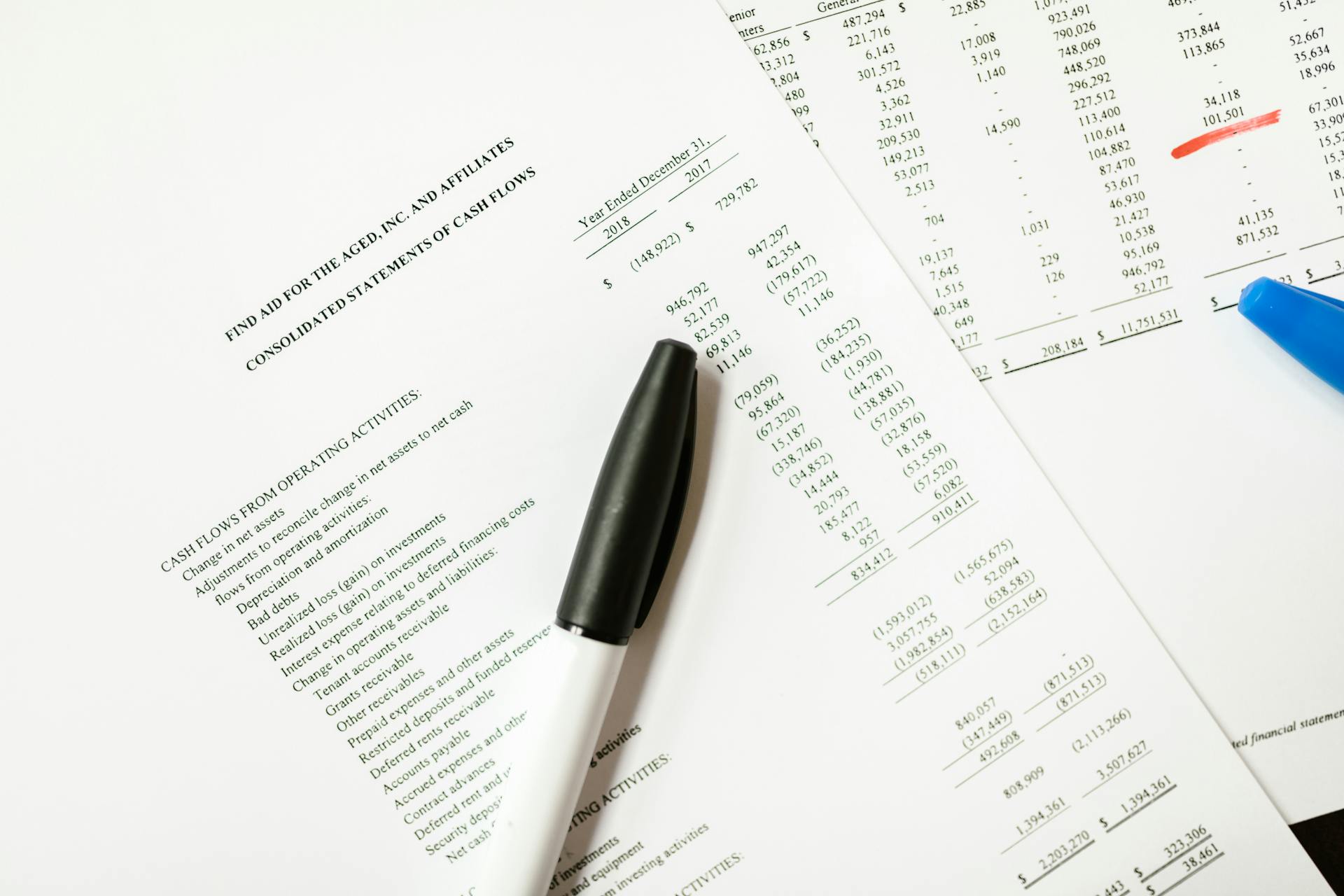

Depreciation Schedule

A depreciation schedule is a crucial tool in financial modeling, used to forecast the value of a company's fixed assets, depreciation expense, and capital expenditures. It helps calculate the depreciation of different assets over time.

The schedule typically lists the different classes of assets, the type of depreciation method they use, and the cumulative depreciation they've incurred at various points in time.

To build a depreciation schedule, you need to start with the beginning balance of PP&E, net of accumulated depreciation. From there, you add capital expenditures, subtract depreciation expense, and subtract any sales or write-offs.

Here's a breakdown of the key components of a depreciation schedule:

In a straight-line depreciation method, the annual depreciation is calculated by dividing the remaining book value of the fixed asset by its useful life assumption.

What Is a Schedule?

A depreciation schedule is a crucial tool in financial modeling that helps forecast the value of a company's fixed assets.

It's required to calculate the depreciation expense on the income statement and capital expenditures on the cash flow statement.

The schedule lists different classes of assets, the type of depreciation method they use, and the cumulative depreciation they've incurred at various points in time.

A depreciation schedule helps to account for the fact that different assets lose value at different rates as they are used.

It may also include historic and forecasted capital expenditures (CapEx) to provide a comprehensive view of a company's financial situation.

If this caught your attention, see: Is Cash Flow Statement Different than Free Cash Flow Statement

PP&E Roll-Forward Schedule

A PP&E roll-forward schedule is a crucial component of a depreciation schedule, and it's essential to understand how it works. It's a detailed schedule that tracks the changes in a company's property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) over time.

To build a PP&E roll-forward schedule, you need to have a good understanding of the company's existing PP&E and its remaining useful life. This information is necessary to project new capital expenditures (CapEx) and depreciation expenses. The average remaining useful life for existing PP&E and useful life assumptions by management (or a rough approximation) are essential variables for projecting new CapEx.

Recommended read: Capex in Cash Flow Statement

The schedule will list the different classes of assets, the type of depreciation method they use, and the cumulative depreciation they've incurred at various points in time. The schedule may also include historic and forecasted capital expenditures (CapEx).

Here's a breakdown of the net change in PP&E:

- Beginning balance of PP&E, net of accumulated depreciation

- Add capital expenditures

- Subtract depreciation expense

- Subtract any sales or write-offs

The final total should be the ending balance of PP&E, already net of accumulated depreciation.

For example, the net PP&E balance for each period can be shown as follows:

This schedule helps to calculate the differences in depreciation expense and capital expenditures over time, providing a clear picture of a company's PP&E and its impact on the financial statements.

Amortization and Depreciation

Depreciation and amortization are accounting methods to calculate the diminishing value of an asset over time.

The primary difference between depreciation and amortization is that depreciation measures the loss of tangible assets, such as industrial machinery and vehicles, while amortization measures the lost value of intangible assets, such as patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

You might like: Net Present Value Cash Flows

Depreciation and amortization are non-cash expenses that reduce a company's earnings each year, but they don't negatively impact the operating cash flow of a business because they are added back to the net income or earnings of the business.

Depreciation is usually shown as an indirect, operating expense on the income statement, and it can be a benefit to a company's tax bill because it's allowed as an expense deduction and lowers the company's taxable income.

The impact of depreciation and amortization on the balance sheet is that a company uses cash to pay for an asset, which initially results in asset transfer, and then depreciation expense gradually writes down the value of a fixed asset so that asset values are appropriately represented on the balance sheet.

To calculate free cash flow, you can add back depreciation and amortization expenses to the net income and then subtract Net PPE and acquisitions, or simply subtract Net PPE from Operating Cash Flow (CFO).

Discover more: Balance Sheet and Cash Flow Statement

Financial Statement Effects

Depreciation on the balance sheet is a straightforward process - a company uses cash to pay for an asset, which initially results in asset transfer. This asset, like a fixed asset, doesn't hold its value over time, so its carrying value needs to be gradually reduced.

To do this, a company uses depreciation expense, which writes down the value of the fixed asset over its useful life. This process is essential for accurately representing asset values on the balance sheet.

The depreciation expense is usually shown as an indirect, operating expense on the income statement, reducing a company's gross profit alongside other indirect expenses like administrative and marketing costs. This is an allowable expense that can be a benefit to a company's tax bill, as it lowers their taxable income.

Here's a breakdown of how depreciation affects the financial statements:

Examples

Let's take a look at some examples of depreciation in action. In one example, a company, OE, invests $10 million in a factory with machinery to produce wrenches, and it depreciates its factory by $1 million yearly over a 10-year period. This means that in the first year, OE expenses its earnings by $1 million for this investment.

You might like: 10 Fiannce Ratios from Financial Statement

The useful life of the factory is 10 years, and the company depreciates it by $1 million each year. This is a straightforward example of the straight-line method of depreciation. The result is that the company's earnings are reduced by $1 million each year for 10 years, and the asset's value on the balance sheet is reduced by the same amount.

Here's a breakdown of the depreciation calculation for OE's factory:

This is just one example of how depreciation can affect a company's cash flow statement. In another example, a company, NE, invests $10 in R&D to create software, and it expenses the entire amount in the first year, with no impact on the balance sheet. This is an example of a company investing in intangible assets, which are not reflected on the balance sheet.

For another approach, see: Balance Sheet Income Statement and Cash Flow

Accounting and Taxes

Depreciation is a crucial concept in accounting and taxes, and it's essential to understand how it affects a company's cash flow statement.

Depreciation is the gradual reduction in the recorded value of a fixed asset over its useful life, and it's a non-cash item that reduces taxable income and net income.

The recognition of depreciation on the income statement reduces taxable income, leading to lower net income.

A company's depreciation expense is typically embedded within either the cost of goods sold (COGS) or operating expenses line on the income statement.

Depreciation expense is treated as a non-cash add-back on the cash flow statement since no real outflow of cash has occurred.

The depreciation expense reduces the book value of a company's property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) over its estimated useful life.

Here's a breakdown of the accounting entries associated with depreciation:

In our hypothetical scenario, the company is projected to have $10mm in revenue in the first year of the forecast, 2021, with a revenue growth rate that decreases by 1.0% each year until reaching 3.0% in 2025.

Explore further: Deferred Revenue Cash Flow Statement

Accounting

In accounting, depreciation is a crucial concept that helps businesses accurately reflect the cost of their assets over time. Depreciation is the gradual reduction in the recorded value of a fixed asset on the balance sheet due to wear and tear.

The matching principle in accrual accounting requires that expenses be recognized in the same period as the coinciding economic benefit is received. This means that the purchase of a fixed asset, also known as a capital expenditure (Capex), must be capitalized rather than expensed in the period incurred.

Fixed assets, such as property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), provide benefits for more than one year, so their cost is allocated across their useful life. This is a more accurate representation of a company's operational performance.

Depreciation spreads the expense of a fixed asset over the years of its estimated useful life. For example, if a company buys a vehicle for $30,000 and plans to use it for five years, the depreciation expense would be divided over five years at $6,000 per year.

A different take: Accounting Profits and Cash Flows Are Generally

The accounting entries for depreciation are a debit to depreciation expense and a credit to fixed asset depreciation accumulation. Each recording of depreciation expense increases the depreciation cost balance and decreases the value of the asset.

Depreciation reduces the book value of a company's PP&E over its estimated useful life, and it is recognized as an operating cost on the income statement. However, it is treated as a non-cash add-back on the cash flow statement since no real outflow of cash has occurred.

Companies seldom report depreciation as a separate expense on their income statement, so it's best to check the cash flow statement or footnotes section to obtain the precise value of a company's depreciation expense.

Taxes

Depreciation can significantly reduce taxes, ultimately increasing a company's net income. This is because depreciation is added back into the operating cash flow, resulting in a higher amount of cash on the cash flow statement.

Taxes can be reduced by using depreciation to account for the loss of value in assets over time. This is a key concept in accounting and taxes.

Depreciation does not negatively affect a business's operating cash flow. It's actually a way to spread the cost of an asset over its useful life.

Companies can choose to finance the purchase of investments in various ways, including loans or debt. Regardless of the method, the actual cash paid out for the fixed asset will be recorded in the investing cash flow section of the cash flow statement.

Depreciation is a crucial factor in calculating a company's operating cash flow.

Special Considerations

Return on equity (ROE) is an important metric that's affected by fixed asset depreciation. This means that as assets lose value over time, the return on equity for shareholders decreases.

A fixed asset's value will decrease over time due to depreciation. This affects the value of equity since assets minus liabilities are equal to equity.

Depreciation also affects another financial metric, EBITDA. Analysts use EBITDA as a benchmark metric for cash flow.

EBITDA is calculated by adding interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization to net income.

For your interest: Equity Market Analysis

Tax Expense

Tax Expense is a crucial aspect of accounting, and it's essential to understand how it works.

In the US, companies can use the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) schedule to depreciate fixed assets for tax purposes. The MACRS schedule is promulgated by the IRS and is used to calculate tax depreciation expense.

Accelerated depreciation has a significant benefit - the present value of the tax shield from tax-deductible depreciation is larger when the depreciation is accelerated.

To calculate tax depreciation, we select a "property class" from the MACRS schedule that most closely ties to the useful life we assumed in calculating book depreciation.

We then use HLOOKUPs on the MACRS schedule to compute tax depreciation expense.

In our model, we have a toggle that allows us to select either book (straight-line) depreciation or MACRS depreciation as our tax depreciation of new fixed assets.

For simplicity, we set tax depreciation of existing fixed assets equal to the book depreciation of such assets.

This means our total tax depreciation equals our total book depreciation, and there is no deferred tax impact related to depreciation.

Here's an interesting read: How Does Income Tax Impact Cash Flow Statement

Frequently Asked Questions

Is depreciation an operating activity?

Yes, depreciation is considered an operating expense, as it's a normal part of business operations. It's recorded as an expense to reflect the asset's gradual loss of value over time.

Where does depreciation go on cash flow statement direct method?

Depreciation is not included in the statement of cash flows using the direct method, as it's a noncash expense. It's excluded from the cash flow statement to provide a more accurate picture of a company's cash inflows and outflows.

Sources

- https://www.wallstreetprep.com/knowledge/depreciation/

- https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/financial-modeling/depreciation-schedule/

- https://einvestingforbeginners.com/depreciation-and-amortization-daah/

- https://macabacus.com/operating-model/depreciation-expense

- https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/080216/how-does-depreciation-affect-cash-flow.asp

Featured Images: pexels.com