The trade-off theory of capital structure suggests that companies face a trade-off between the benefits and costs of debt and equity financing. This theory is based on the idea that companies can reduce their cost of capital by issuing debt, but at the same time, they increase their risk of bankruptcy.

Companies with a high level of debt may face a higher risk of default, which can lead to financial distress and potentially even bankruptcy. This is because debt holders have a claim on the company's assets in the event of liquidation, which can leave shareholders with little to no value.

Firms with a high debt-to-equity ratio may also face higher costs of capital, as investors demand a higher return to compensate for the increased risk. This can make it more difficult for companies to raise capital and invest in new projects.

Ultimately, the trade-off theory suggests that companies must balance the benefits of debt financing against the potential costs, including the risk of bankruptcy and increased costs of capital.

Take a look at this: Car Loans during Bankruptcy Chapter 7

What Is Trade-off Theory?

Trade-off theory suggests that a company's capital structure is determined by weighing the benefits of debt financing against its costs.

Debt financing offers tax benefits, as interest payments are tax-deductible, but it also increases the risk of default and bankruptcy.

The trade-off between debt and equity financing is a delicate balance, as too much debt can lead to financial distress, but too little debt can limit a company's growth opportunities.

What Is a Trade-off Theory?

Trade-off theory is a concept that helps us understand the difficult decisions we face in life. It's all about making choices between competing values, goals, or outcomes.

A trade-off is essentially a compromise between two or more things that are mutually exclusive. For example, if you want to travel more, you may have to sacrifice time with family and friends, or vice versa.

In economics, trade-offs are often seen in the production process, where increasing one output, like cars, might require reducing another output, like bicycles. This is because resources, like labor and materials, are limited.

Trade-offs can also be seen in personal finance, where choosing to save for retirement might mean putting off buying a new car.

What Is Trade-off Theory?

Trade-off theory suggests that as one factor increases, another factor must decrease. This is often seen in the design of products, where a larger size might mean a heavier weight.

In economics, trade-off theory is used to understand the relationship between supply and demand. As the supply of a product increases, the price tends to decrease.

The concept of trade-off theory is not limited to economics, but can be applied to various aspects of life. For instance, if you want to travel more, you might have to sacrifice some comforts, like a smaller living space.

In the context of product design, trade-off theory can help designers make informed decisions about how to allocate resources. For example, if a company wants to increase the battery life of a device, they might have to decrease the device's storage capacity.

Trade-off theory can be seen in the way people make decisions about how to allocate their time and resources. For instance, if you want to spend more time with your family, you might have to sacrifice some work hours or leisure activities.

Broaden your view: Capital Budgeting Decisions Include

Key Concepts

The trade-off theory of capital structure is all about finding that perfect balance. It suggests that companies should weigh the costs and benefits of different financing sources, like debt and equity, to achieve an optimal capital structure.

This balance may look different for each company, depending on factors like the industry they're in, their business risk, and the tax environment.

At its core, the trade-off theory is about making a trade-off between two main things: interest tax shields and the cost of financial distress. Companies need to consider how these factors will impact their capital structure.

Using debt financing can give companies quick access to funds at a lower cost of capital, but equity financing provides more flexibility and control over ownership.

Here are some key factors to consider when applying the trade-off theory:

- Industry

- Business risk

- Tax environment

Determining the Optimal Capital Structure

The optimal capital structure is like a balancing act, with debt and equity being two sides of a scale that companies must carefully manage to maintain optimal balance. It's achieved when the marginal benefit of using debt is equal to the marginal cost of using debt.

Consider reading: What Is Optimal Capital Structure

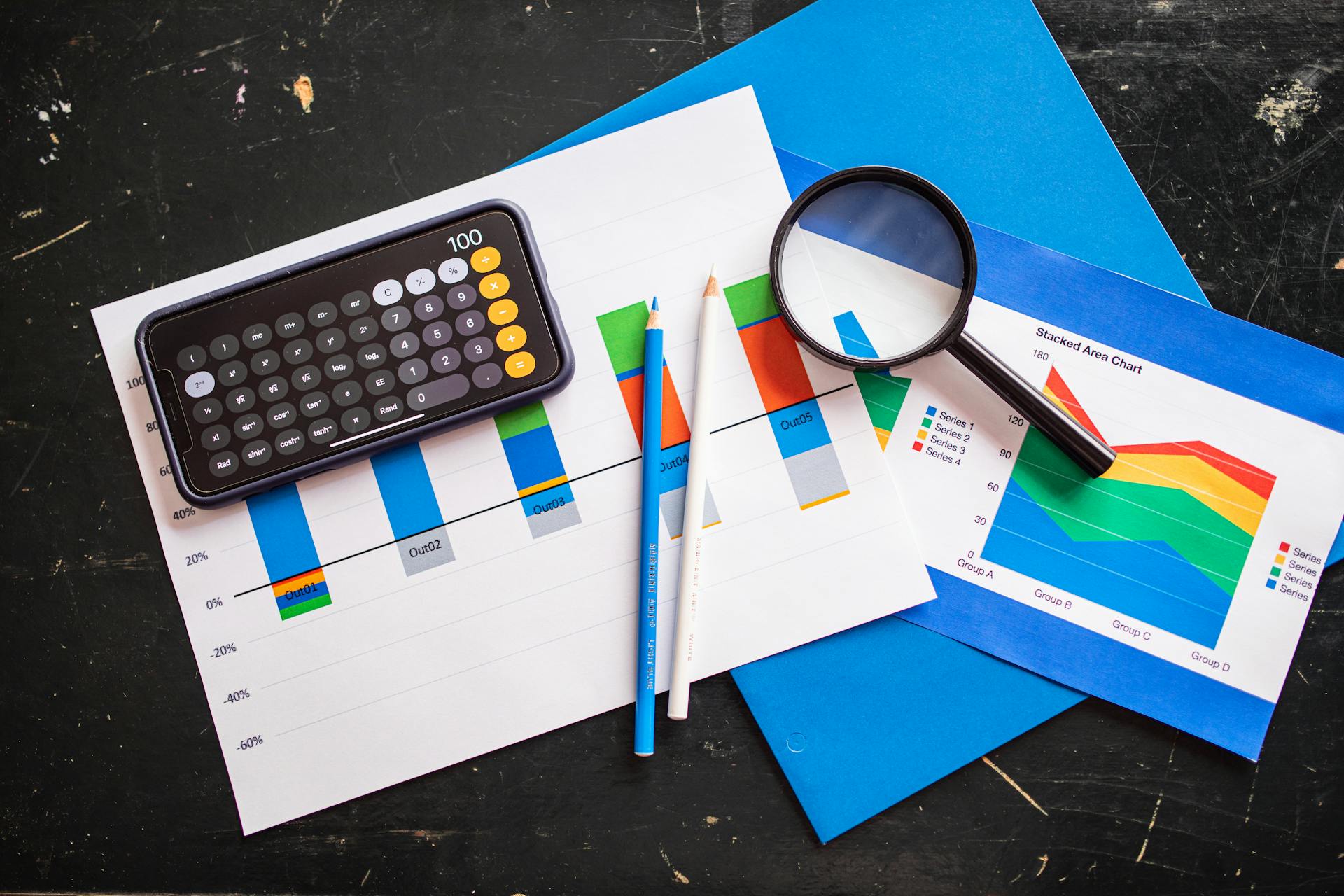

To determine the optimal capital structure, you need to assess the company's financial situation, including its cash flows, profitability, debt levels, and credit rating. This can help identify the company's borrowing capacity and risk tolerance.

You should also analyze the costs and benefits of debt and equity financing, including interest rates, tax implications, dilution of ownership, and flexibility of financing. This can help determine the most cost-effective and suitable financing mix for the company.

The optimal capital structure may also be influenced by the company's industry and market conditions, including competition, regulatory environment, and macroeconomic factors. These factors can affect the company's risk profile, growth prospects, and financing needs.

The optimal capital structure should take into account the company's growth and investment plans, including potential acquisitions, expansion into new markets, and R&D initiatives. These plans can impact the company's financing needs and risk profile, and may require a more flexible or diversified financing mix.

Here are some key factors to consider when evaluating the company's industry and market conditions:

- Cost of financial distress and bankruptcy

- Tax benefits

- Market conditions, including interest rates and investor sentiment

These factors can affect the company's ability to raise debt financing and its overall risk profile.

The target capital structure can be defined as a desirable proportion of equity to debt. The target capital structure determines the ways of acquiring additional capital. Companies can calculate their target capital structure in three ways:

1. Using current capital structure

2. Using competitors' capital structure

3. Using the capital structure based on the target debt-to-equity ratio

The optimal capital structure is when the value of the company is maximized. Every company will have its own optimal debt to equity ratio, as it is dependent on a number of particular factors, including business risk, tax situation, and many others.

You might enjoy: The Optimal Capital Structure Has Been Achieved When The:

Model Limitations and Alternative Theories

The trade-off theory of capital structure has its limitations. The model assumes that debt financing is advantageous because interest payments are tax-deductible, but this may not always be the case.

The trade-off model relies on several simplifying assumptions, such as perfect capital markets and homogeneous investors, which are not reflective of reality. Financial markets are complex and imperfect, and investor preferences and behaviors can vary significantly.

Readers also liked: Can You Get in Trouble for Not Paying Medical Bills

The trade-off model may not be applicable to all companies or industries, as different companies may have different risk profiles, borrowing capacity, and capital market conditions. Companies in emerging industries or with limited track records may face greater difficulty in securing debt financing.

Here are some of the key limitations of the trade-off model:

- Overemphasis on tax benefits

- Simplistic assumptions

- Limited applicability

- Lack of consideration for non-financial factors

- Inability to predict optimal capital structure

- Contradicting empirical evidence

Fortunately, there are alternative theories of capital structure that can provide a more comprehensive understanding of a company's financing decisions.

Model Limitations

The trade-off model, while a useful framework for understanding capital structure, has several limitations that can make it less effective in real-world applications.

One of the main limitations is the overemphasis on tax benefits, which may not always be the case. In some instances, the tax benefits of debt financing may be offset by higher interest rates or other costs.

The trade-off model relies on several simplifying assumptions, such as perfect capital markets and homogeneous investors, which are rarely found in reality.

Recommended read: Brk.b Outstanding Shares

Financial markets are complex and imperfect, and investor preferences and behaviors can vary significantly, making these assumptions unrealistic.

The trade-off model may not be applicable to all companies or industries, as different companies may have different risk profiles, borrowing capacity, and capital market conditions.

Companies in emerging industries or with limited track records may face greater difficulty in securing debt financing, limiting the model's applicability.

The trade-off model focuses primarily on financial considerations, such as tax benefits and costs of financial distress, but may not take into account non-financial factors, such as reputation, corporate governance, and social responsibility.

These non-financial factors can also influence a company's financing decisions, making the model less comprehensive.

The trade-off model provides a framework for analyzing the costs and benefits of debt and equity financing, but it does not provide a definitive answer to the optimal capital structure.

Companies must still make their own judgment based on their unique circumstances and strategic objectives.

Empirical evidence contradicts the traditional trade-off theory of capital structure, which predicts a positive relationship between earnings and leverage.

Intriguing read: Nonprofit Debt Consolidation near Me

Alternative Theories

Companies often prioritize internal funds first, then debt financing, and equity financing as a last resort, reflecting a conservative approach to financing decisions.

The Pecking Order Theory suggests that companies rely on internal funds before seeking external financing sources.

Management may choose a financing mix that benefits them personally, rather than what is best for the company as a whole, according to Agency Theory.

Companies use different signals, such as dividend payments or stock buybacks, to convey important information to investors about their financial health and prospects, as proposed by the Signalling Theory.

Market conditions can influence a company's financing mix, with companies issuing equity financing when stock prices are high and debt financing when stock prices are low, as stated by the Market Timing Theory.

Companies with excess cash flows use debt financing to limit the ability of managers to waste resources, providing discipline to management by constraining their ability to make wasteful decisions, as per the Free Cash Flow Theory.

Consider reading: What Happens When a Stock Splits

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between trade-off theory and pecking order theory?

The trade-off theory predicts a positive relationship between firm age and debt, while the pecking order theory suggests that older firms require less external financing due to retained earnings. This difference in perspective affects how firms approach debt and financing decisions.

Sources

- https://capital.com/trade-off-model-of-capital-structure-definition

- https://soleadea.org/cfa-level-1/optimal-capital-structure

- https://ouci.dntb.gov.ua/en/works/4vw5mw1l/

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Trade-off_theory_of_capital_structure

- https://www.wallstreetprep.com/knowledge/trade-off-theory/

Featured Images: pexels.com